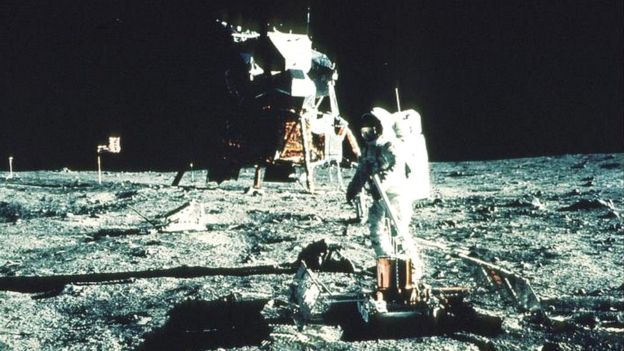

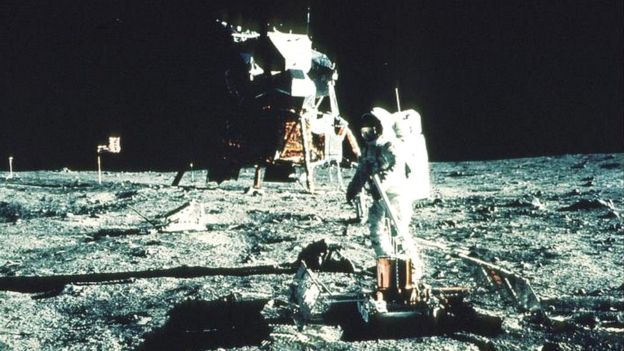

When Apollo XI arrived on the Moon in 1969 and astronaut Neil Armstrong made his "great leap for humanity", everything seemed lost to the Soviet Union.

Millions and millions of people around the world watched those images on television. And in popular history, the United States became the winner of the space race against the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Why now everyone wants to go to the Moon like in the Cold War era?

But to think that is a mistake: the real pioneers of space exploration were the Soviet cosmonauts and much of the advances that are now used in the International Space Station (ISS) are due to the knowledge and innovations of the Soviet Union.

That is the conclusion of the BBC documentary "Cosmonauts: how Russia won the special race", which agreed to important documents and interviewed protagonists of the extraordinary-and sacrificed-bid between Soviets and Americans to conquer the Universe.

By bringing the first satellite, the first human being and the first orbital station to space, the Soviet Union managed to conquer again and again the US, its rival in the Cold War and whose space program, developed under the guidance of the engineer German Wernher von Braun, was more sophisticated and had more funds.

But how did he do it?

The "founding father" of the Soviet program

The origins of the space program of the USSR can be found in the ruins of the Second World War.

When the Americans launched the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki a new world order was born, in which power and influence would not be measured in terms of human effort, but of technological advances.

If the USSR wanted to have international influence, it had to go back quickly to the enormous advantage that the US had taken from it.

In just four years, the Soviets produced their own atomic bomb. "As it was much heavier than the American, they had to develop a more powerful rocket that transported it, which ended up impacting the space program," Gerard de Groot, a professor of modern history at the University of San Andrés, explains to the BBC. in the United Kingdom.

And the person who was tasked with the task was engineer Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.

In 1939, the leader of the USSR Joseph Stalin had declared him an enemy of the State and sent one of the terrible labor camps (or Gulags), where he was expected to die. But faced with the need for brilliant minds at the beginning of the Cold War, he decided to give it another chance.

"Korolev was not a scientist, but a management genius: he was a leader, an inspiring figure, a politician who knew how to move the levers of power and turn goals into reality," Asif space history specialist tells the BBC. Siddiqi, from Fordham University in New York.

Moreover, in the Soviet Union they considered it so strategically important that, to protect it from any assassination attempt, they kept their identity a secret until their last days. He was known simply as the "chief designer".

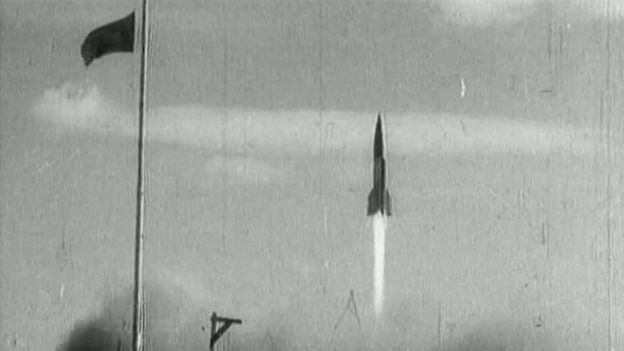

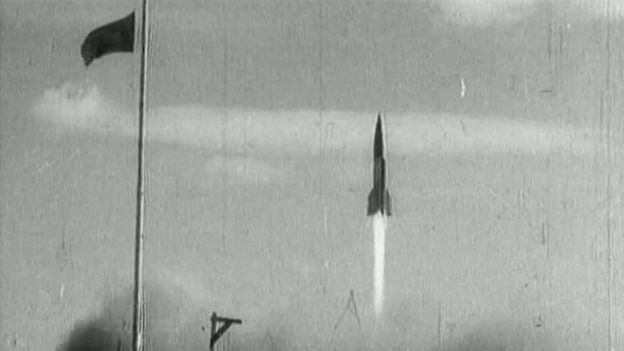

In 1957, Korolev concluded his masterpiece, the R-7 Semyorka rocket, which was nine times more powerful than any other launcher created until that time.

After several failed attempts, the R-7 was successfully tested: it managed to fly 5,600 kilometers to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was the first intercontinental ballistic missile and, with it, Korolev turned the Soviet Union into a global superpower.

However, the fate of the R-7 was not to become a weapon. "As a missile it was bad, it took a long time to prepare it for takeoff, while other more efficient rockets were being developed, the R-7 was dedicated exclusively to space exploration," the former Soviet cosmonaut Georgei Grechko told the BBC.

The Sputnik and Laika

Once he had an apt rocket, Korolev wanted to be the first to prove that space travel was possible. To that end, its engineers developed a simple satellite, the Sputnik.

It was just a radio transmitter covered by a metal sphere.

On October 4, 1957, Sputnik was placed in orbit and began sending radio signals to Earth, a "beep" that the Americans endeavored to decode but did not actually contain any messages.

The world was fascinated. Enthusiasts formed long lines before the telescopes available to see the "second moon" crossing the sky.

The Sputnik was a propaganda masterpiece and now the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev wanted more: he asked Korolev for another large space mission for the commemorations of November 7, the anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917.

The period of about a month seemed impossible. However, on November 3, 1957, the Soviet Union sent another satellite into space, but this time with a passenger on board: Laika, a street dog found in Moscow.

For a long time the Soviets claimed that the dog survived in orbit for several days, but in 2002 they admitted that the climate controls failed and the animal died in just six hours due to overheating.

However, Laika gave the Soviets another propaganda victory and the Americans another headache.

"In the United States they believed that if the USSR had been able to take an animal into space, it would soon be able to send a human being into orbit," explains the historian De Groot.

The smile of Yuri Gagarin

In the early 1960s, 20 potential cosmonauts were secretly trained in a rural area of Russia, including the young Alexei Leonov.

"Every day we ran 5 kilometers and swam 700 meters, we also jumped in parachutes, I got to do 200 jumps," Leonov tells the BBC.

But in addition to physical training, cosmonauts had to prepare for the rigors of space.

They must be able to withstand the enormous force of takeoff and landing. They were locked for days in noise-proof rooms to experience psychological isolation. And worst of all was the preparation for the eventuality that the capsule began to spin without control in space.

"It was very difficult to put up with," recalls former cosmonaut Georgei Grechko. "Some would turn pale, others green, and then, as we used to say, they would show others their dinner: they would vomit."

The preselection of the first human being that would go to space was reduced to two names: Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov.

"Korolev ended up choosing the peasant's son Gagarin," says Grechko. "We thought that the smartest and the best educated was Titov, but the boss considered aspects that we, as engineers, had not thought about: how handsome the candidate was, his smile, and he was right."

The "chief engineer" knew that if the mission was a success, Gagarin's face would be on the front pages of all the newspapers in the world.

On April 12, 1961, Gagarin arrived where no human being had arrived before: the orbit of the Earth. On board the Vostok capsule, he took a turn around the poses in one hour and 48 minutes.

"I'm looking at the Earth," he said when communicating with the control center. "I see the colors of the landscape, forests, rivers, clouds, everything is so beautiful."

Gagarin was received as a hero in the Soviet Union and traveled the world wearing his triumphant smile. It was the embodiment of the Soviet Union's dominance in the space race.

Follows of feats

The Americans desperately needed a triumph over the USSR and President John F. Kennedy set an ambitious goal: "We chose to go to the Moon in this decade."

With its booming economy, the US he could invest large sums of money in the development of a lunar program. On the contrary, in the USSR the leaders were not willing to finance such an expensive adventure.

"My father told Korolev that in the Soviet Union there were other priorities: to produce more food to end the shortage and build more houses," the BBC's Sergei Khrushchev, son of the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, told the BBC.

"He did not want to spend all that money on beating the Americans in the race to get to the Moon."

Instead, Korolev launched a series of less expensive missions to low Earth orbit, each of which reported a propaganda victory. Among them are two of 1963: the longest orbital flight to date (five days) and the first woman to go to space, Valentina Tereshkova.

On March 18, 1965, another milestone would be added: Alexei Leonov became the first human being to make a spacewalk.

"Korolev had told us: 'Just as a sailor on board a ship has to be able to swim in the ocean, a cosmonaut must know how to float in space," recalls Leonov.

On the way to the Moon

Leonov's feat marked the end of the golden age of the space program of the USSR, to which were added a series of tragedies.

On January 14, 1966 Korolev, the inspiring figure of the Soviet exploration of the cosmos, died after routine surgery that could not be recovered.

He was replaced by his second, Vasily Mishin, who lacked the vision and management skills of the "chief designer".

But the worst was yet to come: on March 26, 1968 Yuri Gagarin, the smiling emblem of Soviet space dominance, lost his life during a test flight. It was a national tragedy.

Less than a year later, the N1, the titanic rocket that the USSR would use for its lunar adventure, exploded and left the launch base unused.

With the Soviets out of the race, the Americans achieved what seemed impossible: on July 20, 1969, Apollo XI arrived on the Moon.

The first space stations

The Soviets quickly forgot about the Moon and set a new goal that would resuscitate their space program: colonization. They would look for the way to live and work in space.

On April 19, 1971, they launched into orbit Salyut 1, the first temporary space station in history. It was occupied by three cosmonauts for three weeks. This would be followed by missions and longer stays.

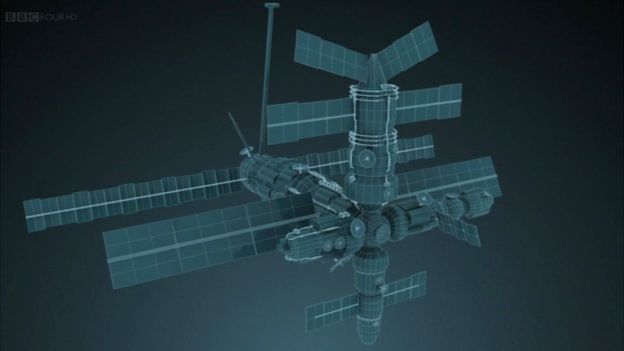

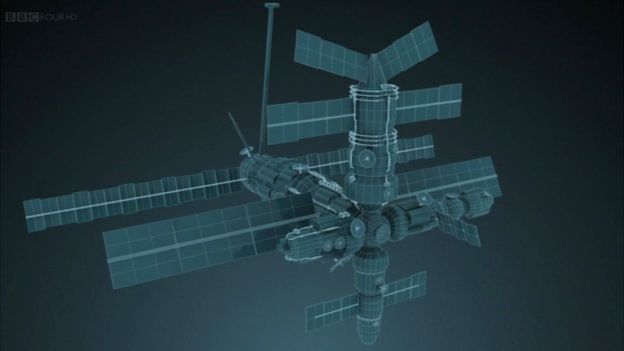

On February 20, 1986, while the Americans were concentrating on short flights with space shuttles, the Soviets placed the first permanent station, the MIR, into Earth orbit, which was completed over a decade.

At 31 meters wide, 19 meters long and 27 meters high, this structure became a huge suspended laboratory, with separate modules for astrophysics, materials science and Earth study.

Teams of cosmonauts visited the station for periods of one year and became true experts in life in space.

A new era of space cooperation

At the end of 1991, while the MIR orbited the planet, the Soviet Union dissolved. The Soviet space program passed into the hands of Russia and the lack of funds threatened its existence.

In Washington, they feared that many aerospace engineers would become unemployed and go to work in Iran or North Korea.

Therefore, the USA he offered Russia to join in the exploration of the Universe and, after decades of rivalry, the two space powers became partners.

It was a convenient relationship for both: Americans would benefit from the cosmonauts' experience in long stays in space, and the Russians would stay afloat with US funds.

As a first step, American astronauts went to live and work at the MIR. Then dozens of representatives from other countries joined.

The International Space Station

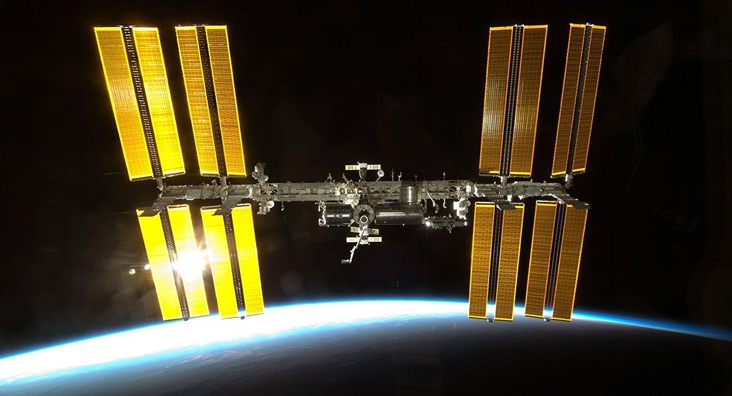

When the MIR was decommissioned and disintegrated upon re-entry to Earth in 2001, its replacement, the International Space Station (ISS), was already being assembled in orbit.

It was the first totally international adventure in the cosmos: 15 space agencies collaborated to build a structure four times larger than the MIR.

"We had a great knowledge of long stays in space, how they affected a person, so we joined the project and shared everything we knew," the former cosmonaut Alexander Lazutkin tells the BBC.

Certainly, the ISS is the testament to the achievements of the USSR space program during 50 years of exploration of the Universe.

Its life support system is based on those of the Salyut and MIR stations. The costumes that are used are "made in Russia", updated versions of the one used by Alexei Leonov in the first spacewalk in history.

And since 2011 the only way to reach the ISS is through a Soyuz capsule mounted on an R-7 rocket, both technologies that, although modernized, designed by Sergei Korolev half a century ago.

"The USSR lost the race to reach the moon, yes, but the continued presence of the human being in orbit is due to the Soviet and Russian determination to conquer space," concludes the American historian Gerard de Groot.